A clear theme emerged from several speeches, an informative panel discussion, and many lively dinner conversations: The AYC experience is life changing.

AYC is succeeding in its goal to provide a forum for meaningful exchange between Chinese and Western youth. It is exactly this understanding from one-on-one interaction and education that will improve relations between countries and nations in our increasingly globalized world.

June 15-19, we have our final lessons. Some classes were easy to say good-bye, but I had trouble closing the lesson with the students, and some students didn’t even want to leave the classroom.

AYC Educational Ambassadors Ethan Martinez and Caitlin Simcik ventured to Yunnan for Spring Festival. We just had to share their incredible footage.

To the Chinese, there are three important meanings behind the Mid-Autumn Festival: 1) gathering, as family and friends reunite to celebrate, 2) thanksgiving, to appreciate the life-giving harvest, and 3) prayer, in order to bestow both blessings and good fortune upon parents, babies, and lovers.

So, now you’ve been in China for about two weeks and you’ve had an inordinate amount of cafeteria food plus one or two lavish feasts at your new school. Where do you go from here? Well, if you want to cut your chops on the diverse cuisines that make up “Chinese food”, you should take a look at China’s Yelp: Dianping. If you don’t want to throw your gastronomical dreams to the winds of fate and your late night strolls around town, check out this site.

For those of you who aren’t quite ready to navigate a website entirely in Chinese, these two guides will help you get where you want to go.

http://beijingfoodbible.wordpress.com/2012/03/31/where-do-beijingers-eat-a-quick-dianping-tutorial/

http://www.lifeonnanchanglu.com/2013/12/unlocking-dianping-english-guide-to.html

This year was a long one, but many of the awesome AYC participants have finished out their academic year! The above collage only showcases a few of the 150+ teachers spread throughout China with their students. Many have already left for their next journey, others are teaching farther into the summer, but one thing remains true: AYC is immensely proud of it’s inaugural class of Ameson Year in China!

Salute — the AYC Class of 2013-2014!

Have you ever mused over the possible deep meaning of the choice English names your students chose? Have you ever wondered why your Chinese name sounds really strange when translated into English? Well below is an introduction to some of the more interesting naming practices.

- How many names?: Historically, socially enfranchised individuals could have different names at different stages of their life and stylized versions of them for different uses. Sun Yat-Sen, the founding father of the Chinese Republic, had eight, not including a large number of pseudonyms used while in hiding.

- 1, 2, or 3?: In traditional China there was a strong emphasis on having as many children as possible. This led to some pretty large numbers of children that could sometimes be hard to keep track of. Enter the numbers. Using a number after a name indicates the individual’s position in line; in the case of Su Forty-Three, a famous rebel in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) who seems to be pretty far down the list. A common usage today is referring to oneself relative to one’s brothers and sisters. The third child in a family would be called “old three.”

- You want me to be what?: In China, names express a parents desire for a child or describe characteristics the child may have. In rural settings, embarrassing physical features or associations are common. If a child doesn’t turn out just as the parents wanted, they may keep the name they planned on anyway. A tragic young male character in “The World” by director Jia Zhangke goes by the name “Maiden Number Two” because his parents had hoped that their second child would be a girl.

“I don’t think the magic has died down, really. Everywhere I go on campus, someone will run up to me and ask me how I am or say good afternoon. Many students are not afraid to just come up and ask me random questions, like, “Where are you from?” or “Do you have a boyfriend?”

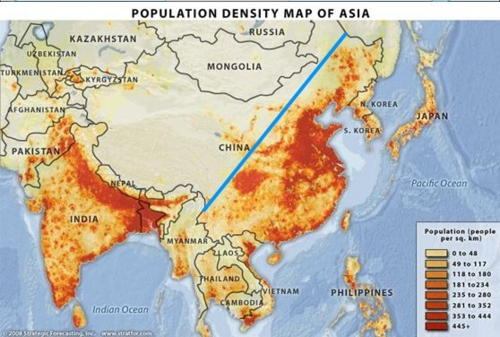

Proposed in 1934 by geographer Hu Huanyong, the Heihe-Tengchong line is not China’s newest highspeed rail line, but an interesting artifact of human geography. This line divides China roughly into two halves in terms of geographic area (57% to the West, 43% to the East), but nearly all the population - a whopping 94% - resides to the East of the line.

Impressive though these numbers may be, what’s perhaps more impressive is that despite having a population density lower than all but 27 countries, the western half of China would still be the 16th largest country in the world by population, just below Germany.

As you can see from the map, China’s population density is highly concentrated between the Yellow River (黄河) to the north and the Yang-tze River (长江)to the Souh, as well as along the coast. The large red spot just east of the line represents a very fertile agricultural area sometimes referred to as “China’s breadbasket” and includes the megacities Chengdu and Chongqing. Most of China’s West is arid, high up in the mountains, or both, making it difficult to sustain dense populations.

“Exploring the city with my students has definitely given me the experience that I’ve had,” Mary says. “I wouldn’t trade it for the world.”

If your Chinese is at a moderate level, there’s a good chance you’ll have learned the word 老百姓 (lit. “old hundred names” or “the common people”). What you may not have learned is that the word has completely flipped in meaning over the last hundred years. Throughout most of Chinese history, common people did not have surnames. Surnames (姓) were reserved only for the aristocracy, and the “hundred” (百) was a way of referring to all of the various family lines as a unit. Thus, 百姓 refers to the nobility, not the common people. However with the end of the feudal system, the universalization of surnames, and progressive social atmosphere brought by the communist revolution, the term took a 老 (“old”, which to this learner seems to add both respect and familiarity) and began to refer to “the people” as a whole.

Visit Huanghshan with AYC in 90 seconds! The video of AYC'ers on Mt. Huangshan features photography by AYC’s own Fred Bane, and takes viewers from sunset to sunrise in the mountain region. Discover one of the beautiful wonders of China with participants!

Victoria Caitlin Evans, placed in Longwan High School in Wenzhou, brings creativity to the classroom. When teaching her Grade 1’s (17 year olds) she prioritizes student involvement, creating fun lessons that stretch students use of the English language and promotes full class participation. Her method is simple, “I have an outline of what I want to happen, tell them, and then we work through it together. For example, the last lesson I did we played scrabble with some homemade scrabble letters I made. I explained to them how to play, and as they are playing/writing/talking /singing (whatever we are doing that day), I make my rounds and just help them out, whether that’s keeping them on task or answering questions.”

Caitlin has found many ways to adjust to her new home in Wenzhou. She mentions that the other AYC'ers in the area have helped her adjustment to China life, as well as her awesome students. Some adjustments have stemmed from ingenuity: she was able to overcome a lapse in communication with her school by increasing her involvement around the school. Other hurdles proved to be more difficult. Upon arriving into China, aside from the universal barriers of language and culture for foreigners, Caitlin has faced “an apartment fire, a typhoon, small earthquakes, late paychecks from [her] school, and worst of all, [her] school lost a student to depression in the fall.” Facing these issues in ones native country can be difficult– in a foreign land they can be down-right soul crushing, but Caitlin has passed through the darker spots head-held high and thankful for this experience. “It’s going to be a bittersweet good-bye in July, but I’m grateful to have been able to come to Longwan, (or as I like to call it #Winning-zhou) and -cheesy warning- I’ll always have a special place for it in my heart forever.“

Before 2008, International Labor Day was one of three long holidays during the year, along with Spring Festival and National Day. Like every other so-called “Golden Week” this inspired enormous crowds, jacked up prices, and severe shortage of resources in tourist areas. Around 2008 the government realized that if the holidays were a bit more spread out workers would be happier and fewer old ladies would get punched in the face for the last train ticket. And so, Labor Day was reformed from a week long holiday into a three day one, and three other holidays were given official recognition.

These holidays, Qingming (Tomb Sweeping Festival), Duanwu (Dragon Boat Festival) and Middle Autumn Day, were not new creations, but rather traditional holidays that were reinstated in 2008. These holidays all enjoyed official status during the Republican period (1912-1949), but saw it revoked with the rise of a new government determined to wipe out old superstition. However, recent years have seen interest in preserving traditional culture rekindled in China, and these holidays have accordingly been transformed from something to be ideologically reviled to a way to preserve and continue aspects of China’s unique cultural heritage like respect for ancestors, love of nature, and punching old ladies in the face.

The internet may finally be putting an end to problems getting taxis in China: two new(ish) apps have made it possible to call a taxi to your spot in minutes via your smart phone. 嘀嘀打车 (Android and IOS)and 快的打车 (Android) allow users to input their destination either by text or by voice and sends that information to drivers nearby. After a driver accepts the call, the phone number and license plate of the driver is sent to the user. A little Chinese is required, but you can store commonly used addresses and send the request by text, so if a friend helps you set it up you can easily learn how to use it.

Although it may soon be difficult to get a cab without them, these apps saw slow growth since their release in 2012 – the entire city of Beijing had only 15 drivers using 嘀嘀打车 on the day it went online! The companies behind these apps offered cash bonuses to drivers who referred others to the app, and phone minutes to cover the significant data charges drivers incur, but it wasn’t until this year when they started offering 10 yuan discounts on taxi rides that the two apps really took off.

Of course, there is the ever-present internet problem of how to make this service profitable. Both companies seem to be looking to incorporating online payments as a way to bring in revenue, but neither seems to have a coherent plan. The services are available in major cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Hangzhou etc.) and are continuing to expand, so if they can ever turn a profit, they may be coming to Yuncheng very soon.

Simeon Campbell made it a mission to bring his passion into the classroom and succeeded by not only introducing his students to poetry, but also putting on the very first Poetry Slam at Nanjing Zhong Xue in Jiangyin. Simeon has long written and performed poetry of his own at his native Los Angeles’s DPL Lounge’s open mic nights, and he showed the kids some of his poems, along with other poems by more established authors, to help explain what poetry is like in English.

The day of the slam, Simeon coached his students on the makings of a great performance – body language, projection, and vocal control. Fellow AYC'erKatherine Priddy, played a large roll in helping him organize the event; four other teachers volunteered as judges, ranking participants on a scale of 1-10 for both performance and quality of writing. The students competed for monetary prizes – 100 yuan for first place, 75 for second, 50 for third, and 10 yuan each for four honorable mentions.

In the end the event was an incredible success produced by AYC'ers Katherine and Simeon, and the kids at Jiangyin were able to uninhibitedly express themselves in english in front of their classmates and teachers. Kudos to these AYC'ers!

After inventing the movable type printing press, not a lot of innovation happened in Chinese typography until the invention of the computer. Early attempts to digitize the language included shape-based methods like Cangjie and phonetic-based ones like Zhuyin, but today the most common are Pinyin and Wubi. After six years in China Wubi is still like sorcery to me, so today we’ll just talk about Pinyin. Among Pinyin input systems, the best by far is Sougou.

Earlier Pinyin methods worked character by character, so you had to type wo, select 我, yao, select 要, qu, select 去…. but Sougou and other modern pinyin inputs can interpret entire sentences (woyaoquxuexiao 我要去学校) with impressive accuracy using context clues and data from other users. You can also just type the first letter of each syllable, for example xx pulls up 谢谢, 学校, and 信息 as my top 3. Typing rq for 日期 gives you the date in multiple different formats, and classical poems are indexed as well (try typing llysc!). After some practice I found that I could type in Chinese even faster than in English.

One particularly cool feature for learners of Chinese is that by first typing u you enter an input mode that allows you to break up characters you don’t know and enter them radical by radical. For example, to type 淼, a character made up of three 水s, type u then “shuishuishui” and Sougou will tell you it’s pronounced miao3. NICE.

As many of you are painfully aware, China is a land of many dialects, and people are often unsure of the “proper” pronunciation of a character. So most Pinyin systems today allow for what’s called “fuzzy Pinyin”. In the settings menu you can check boxes indicating the features of your dialect (sh goes to s, h goes to f, n goes to l, etc.).

Last but not least, if you come across a computer that’s typing like this, the computer is in full-width character mode, which you can exit by hitting shift+space or control+space.

ted:

Well, that was easy.

You just learned 8 Chinese words in the cutest way possible.

When TED speaker ShaoLan Hsueh tried to teach her children Chinese, she realized just how hard it is for new learners to grasp. So she created a series of illustrations to make the beautiful, often complex characters easier to remember. It makes learning Chinese … wait for it … Chineasy.

Check this out, an easy way to remember Chinese characters!

China has its own special way of celebrating diversity, but as the song referenced in the title suggests, China is home to a staggering array of ethnic diversity. Nothing you can say about 56 different cultural groups in two paragraphs could really communicate anything, so the only option is to go out there and experience it first hand. Popular destinations for cultural travel in China include Yunnan (Xishuang Bannna and Lijiang) and Guangxi (Yangshuo), which are very accessible but quite touristy. For people who want to get off the beaten track a bit, there are some better options. For Tibetan culture, Western Sichuan is actually a better choice than Tibet, as there are less restrictions both on you the traveler and on the local community. For Miao/Hmong people, Guizhou is working hard to attract tourists but is still full of amazing undeveloped places to visit, and the local culture is extremely hospitable (but be prepared to be drunk every day). Even further afield choices include Ningxia for an interesting mix of East and Central Asian cultures inhabited by the Hui people (Chinese Muslims), and the Nu and Dulong river valleys in the far west of Yunnan near the border with Myanmar. These latter two valleys are very hard to get to, but home to some of the smallest ethnic groups in the country (the Nu and Dulong respectively). If you do not fear the cold, legend has it the far Northeast still has nomadic herders of the reindeer variety. Any true China experience should include at least some time spent in minority areas.